| | |

| By Maziar Razi | |

| Wednesday, 14 January 2009 | |

Chris Harman sides with reactionary Islamic FundamentalistsIf Tony Cliff parts from the basic ideas of revolutionary Marxism and revises Trotsky's permanent revolution, Chris Harman, by extending Tony Cliff's deviation, sides with counter-revolutionary Islamic fundamentalists. This position potentially places the SWP leadership in a united bloc with reactionaries. Chris Harman discusses the theoretical root of his support for the Islamic Republic of Iran and fundamentalism:

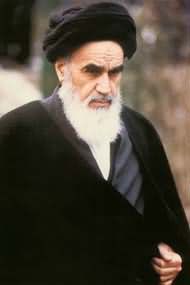

Ayatollah Ruhollah Musavi Khomeini Chris Harman concludes:

Following Tony Cliff's revision of the permanent revolution, Chris Harman absurdly compares Khomeini's regime to "weak communist parties in East Europe" or Jacobins! By doing so, Chris Harman shows that not only is he clueless about the history and class nature of Islamic fundamentalists in Iran, but he also misrepresents Tony Cliff's deviated position. All this is not at all surprising if one looks briefly at another major error in the ideas developed first by Tony Cliff and later built on by his followers. Cliff drew the conclusion that the degeneration of the Soviet Union had led to the establishment of "state capitalism", and later applied this to Eastern Europe and other regimes where capitalism had been abolished and a planned economy had been put in its place. Having stated that these regimes were just another form of capitalism, it appears clear why they see no fundamental difference between a regime such as that in Cuba and the Islamic fundamentalist regime in Iran. Here one can also begin to see why they develop illusions in the Islamic regimes. Thus they look at the superficial aspects that could lead one to see Castro's Cuba and Khomeini's Iran in the same light. As they both have come into conflict at various times with US imperialism then there must be some similarity between them. Instead of looking at the essential aspect of the way the economy works, they look at the outer trappings. Genuine Trotskyists have always defended the planned economy of the Soviet Union in the past and what still remains of it in Cuba today. They fought the Stalinist degeneration, the bureaucracy with all its monstrous features, while defending the centrally planned state owned economy. In Iran the system cannot be compared to that of the former Soviet Union, but if - as the SWP thinks - the Soviet Union was merely a variant of capitalism one can understand how easy it is to fall into the blunder of seeing in the stabilisation of capitalist relations under Khomeini a similar process to what happened under Stalin. It is like confusing oil with water. The two are very different. Down this road one can see how the process of prettifying Islamic fundamentalism can start. Reactionary role of clergy ignored by Chris HarmanUnlike Chris Harman's belief, Khomeini's clique has been part and parcel of the ruling class in Iran for decades. Neither the IRI's leaders, nor its social base have been formed by the "intelligentsia"! The main bulk of the leadership have been big landlords (like Ali Akbar Rafsanjani - the president of the IRI for two terms, and one of most influential and prominent figures today); and the social base of the regime was formed mainly by discontented shanty towns dwellers, urban petty bourgeois and the peasant migrants, etc. Given the predominance of the urban petty bourgeois and the peasant migrants in the early stages of the mass movement, the call of the clergy for "Islamic Justice", "Islamic economics", "Islamic army", and "Islamic state" could immediately find a willing mass base. The point Chris Harman should realise is that, if the bourgeoisie is in power and the state is a bourgeois state, then obviously the fundamental question, according to Marx, Lenin and Trotsky is the destruction of that state and replacing it with a workers' state which can carry out the bourgeois democratic tasks. By this logic, any bourgeois state is utterly reactionary and must be toppled by a revolution. But the SWP argues to the contrary and believes that any "enemy" of imperialism in any underdeveloped country, in the absence of revolutionary proletariat, is objectively "progressive" and is potentially a positive step in the process of growing over to the socialist phase. It is obvious that, if the class character of the state has already become bourgeois (unlike the character of the national bourgeoisie over 100 years ago), then it follows by definition that it has a social base within the bourgeoisie and is therefore also actively supported by at least the upper layers of the petty bourgeoisie. Today, in any of the underdeveloped capitalist countries, in the event of a revolutionary crisis which could threaten bourgeois class rule, one must expect to find in the camp of counter-revolution not only the entire bourgeoisie, but also the upper layers of the petty bourgeoisie, and some of the so called "intelligentsia" are no exception to this rule. In the Iranian revolution of 1979 precisely this scenario took place. The entire resources of the international and national bourgeoisie, orchestrated by the CIA, were mobilised to transfer power to Khomeini as the representative of the capitalist clergy, to safeguard and save the bourgeois state. The shock troops of the counterrevolution were made up of this layer, i.e. the petty bourgeoisie. What Chris Harman misses completely in his analysis of the IRI, is the fact that it is well documented that long before the February 1978 insurrection, important sections of the army, the secret police and the bureaucracy lined up behind Khomeini. US imperialism also intervened directly to bring about a negotiated settlement between the chiefs of the armed forces and the bourgeois-clerical leadership, not to mention many of the biggest bourgeois entrepreneurs who gave Khomeini huge sums of money to organise his "leadership". Given the broadness of the mass movement and its radicalism, the only way that the bourgeois counter-revolution could have succeeded in defeating the revolution was by "joining" it. This could have been possible only by supporting a faction within the opposition to the Shah that could ensure a degree of control over the masses. This was one of the most (if not the most) important factors in placing Khomeini at the head of the mass movement. The reasons why the Shiite clergy, especially Khomeini's faction, was well suited for this task should be obvious. The clergy has always been an important institution of the state, well trained in defending class society and private property. After all, the Shiite hierarchy has been the main ideological prop of the state. Khomeini himself had come from a faction which had already proven its loyalty to the ruling class by helping it in the 1953 coup. It was also the least hated instrument of the state, because it was not a structural part of what it was supporting. Unlike the Catholic Church, it had always kept its distance from the state. Especially because of the post-White Revolution period of capitalist development, the clergy had been relegated to a secondary position. Indeed, because of this, a growing faction within the hierarchy had been forced into a position of opposition to the Shah's regime. This could now be utilised as a passport inside the mass movement. Given the weakness of the bourgeois political opposition, which was not allowed to operate under the Shah, the clergy, with its nationwide network of mullahs and mosques, provided the strong instrument-cum-party necessary for "organising" and channelling the spontaneous mass movement. It could also provide the type of vague populist ideology needed to blunt the radical demands of the masses and to unite them around a veiled bourgeois programme. To deny, therefore, even today, as the SWP leadership does, that Khomeini's counter-revolutionary drive coincided with its efforts to place itself at the leadership of the revolution, is to go against all the facts now known to millions of Iranians themselves. To deny also that from the beginning it was helped in these efforts by the ruling classes and their imperialist backers is to misunderstand the main course of events in the Iranian revolution. It is, therefore, a total mystification to characterise the Iranian revolution as a popular anti-imperialist revolution led by "petty bourgeois "intelligentsia" or to state that "They [the regime] undertook a revolutionary reorganisation of ownership and control of capital within Iran". This interpretation completely misses out the specific counter-revolutionary role of the bourgeoisie and its political tool within the revolution. The political and economic crisis of the 1976-78 period, which set the scene for the mass unrest, was made up of different and contradictory factors. Alongside the mass movement of protests against the Shah's dependent capitalist dictatorship, there were also important rifts inside the bourgeoisie as a whole, both within the pro-Shah sections and between the pro and anti-Shah sections. These bourgeoisie oppositions to the Shah's rule were transformed as the revolutionary crisis grew and deepened: there was, firstly, a movement for the reform of the Shah's state from within the top "modernist" bourgeoisie, which favoured the limitation of the Royal Family's absolute powers and was for a certain degree of rationalisation of the capitalist state. The requirements of further capitalist development themselves necessitated these reforms. This faction had already formed itself within the Shah's single party (rastakhiz - Resurgence) before the revolutionary crisis. It had the support of an important section of the technocrats and bureaucrats inside Iran, and of influential groups within the US establishment. As the crisis deepened, this faction became increasingly vociferous in its opposition to the Shah. It began to use the threat of the mass movement as leverage in its dealings with the Shah. The ousting of Hoveida's government and the formation of Amouzegar's cabinet was a concession to this faction. The development of the mass movement was, however, pushing other bourgeois oppositionists to the forefront. This faction knew that, in order to ride the crisis out, it had to hide behind bourgeois politicians less associated with the Shah's dictatorship. In no other way could it hope to enjoy a certain degree of support inside the mass movement. The re-emergence of the corpse called the National Front and the rise of newly created bourgeois liberal groupings, (e.g. the Radical Movement) were linked to this trend. There was also an opposition to the Shah from within the more traditional sectors of the bourgeoisie (the big bazaar merchants and the small and medium sized capitalists from the more traditional sectors of the industry). The White Revolution and the type of capitalist growth which followed it had also enriched these layers. Nevertheless, they were more or less pushed out of the main channels of the state-backed capital accumulation and hence out of the ruling class. The structural crisis of Iranian capitalism in the mid-1970's had resulted in the sharpening of the attacks by the Shah's state on these layers which still had control over a section of the internal market. This hold had to be weakened, to allow the monopolies to resolve their crisis of overproduction. The consumer goods oriented and technologically dependent industrialisation meant a strong tendency for bureaucratic control of the internal market through the state. To these layers, opposition to the Shah's rule was a matter of a life and death struggle. They could in no way be satisfied with the type of reforms that were being proposed by the other factions. They demanded a more radical change within the power structures. Whilst the reformist factions vehemently opposed any radical change that could shake up the power of the ruling class as a whole, this faction's interests were in no way harmed by demanding no less than the removal of the Shah's regime. As the mass movement grew, it became obvious that this faction could decisively outbid the others. Through the traditional channels of the bazaar economy, it could draw on the support of the urban petty bourgeoisie and the enormous mass of the urban poor linked to it. This faction had, in addition, many links with the powerful Shiite hierarchy. Ever since the White Revolution, the traditional bourgeoisie and the Shiite clergy had drawn closer and closer together. An important lesson drawn by a section of the bourgeoisie after its defeat in 1953 was precisely that, without an Islamic ideology and without the backing of the mullahs, it could never ensure enough mass support to enable it to pose as a realistic alternative both to the Shah and to the left. Bazargan's and Taleghani's Freedom Movement represented this trend. This "party" was now offered an opportunity to save the bourgeoisie in its moment of crisis. The formation of Sharif Emami's cabinet represented a move by the Shah's regime to also include this faction in whatever concessions it had to give. "The government of national conciliation" as it called itself, could, however, neither satisfy the two bourgeois factions, nor quench the mass movement which by now had gathered a new vitality because of the gradually developing general strike. Throughout this period, Khomeini was popular because he appeared to be consistently calling for the overthrow of the Shah. But at the same time he was preparing to reach an agreement with the regime. In fact it was precisely in this period that, with the help of powerful forces within the regime itself, Khomeini's "leadership" was being established over the mass movement. By September 1978, a certain degree of control was exercised which could have allowed a compromise at the top. What put a stop to this was the developing general strike. The stage was thus set for the opening of the pre-revolutionary period of September 1978 to February 1979, marked by the further isolation of the Shah's regime, demoralisation of the army and the police, the radicalisation of the masses and the complete paralysis of the entire bourgeois society because of the very effective general strike. US imperialism and the pro-Shah bourgeoisie were now forced to go a lot further in giving concessions to the mass movement. The removal of the Shah from the scene and the establishment of the Bakhtiar government was in its time and in itself a very radical concession by the dictatorship. It was hoped that in this way the reformist faction, which was already made to look more acceptable, would be strengthened and thus force the more radical faction into a compromise. It was, however, already too late for such compromises. The mass movement was becoming extremely confident of its own strength and the prevailing mood was that of not agreeing to anything less than the complete ousting of the Shah. Furthermore, any politician who tried to reach a compromise with the Shah, immediately lost all support. In fact, even the National Front was forced to renounce Bakhtiar. This explains the so-called "intransigence" of Khomeini's stand. By denouncing Bakhtiar (with whom his representatives in Iran were nevertheless holding secret negotiations) and supporting the mass movement, he was strengthening his own hand vis-à-vis both factions of the bourgeois opposition. He was forcing the more popular figures within these factions to accept his "leadership" and preventing them from reaching any compromises without his involvement. The military circles and the imperialists were also by this time prepared to give up a lot more. There was a growing restlessness within the army. The pro-Shah hard liners were preparing for a coup against Bakhtiar. This would have completely finished off the army and with it the last hope of the bourgeoisie in maintaining class rule. It was becoming obvious that a compromise had to be reached with Khomeini. And that was exactly what took place. Secret negotiations between Beheshti and Bazargan on the one side and the heads of the army and the secret police on the other side were held in Tehran. The arbiter was the US representative General Huyser, whose job was to ensure that the army would keep its side of the bargain. Major sections of the ruling class had been pushed by the course of events, and the encouragement of the Carter administration, to accept sharing power with the opposition. What was hoped was a smooth transition from the top to a Bazargan government. Bazargan had emerged as the acceptable alternative because he was the only one who could bring about a coalition involving both major bourgeois factions, whilst at the same time being more associated with the, by now, more powerful Khomeini leadership. Khomeini was also forced to accept such a deal because this provided the best cover for the clergy's own designs for power. At that time the clergy could not make any open claims to political power. Khomeini, to alleviate the fears of the bourgeoisie, and to keep his own options open within the mass movement, was constantly reassuring everybody that once the Shah was gone he would go back to Qom and continue with his "religious duties". Khomeini was thus allowed to return to Iran from exile and his appointed provisional government was preparing to take over from Bakhtiar. The February insurrection was, however, not part of the deal. Some of the now staunch supporters of the Shah within the chiefs of the armed forces who opposed the US backed compromise, tried to change the course of events by organising a military coup. This resulted in an immediate mass response and insurrection, which was initially opposed by Khomeini. But his forces had to join in later, because otherwise they would have lost all control over the mass movement and with it any hope of saving the state apparatus. The only way to divert the insurrection was therefore to "lead" it. The army chiefs and the bureaucracy were prepared to give their allegiance to Khomeini and his Revolutionary Islamic Council, since this alone could save them from the insurrectionary masses. It was thus that the Bazargan's Provisional Revolutionary Government, as it was called, replaced Bakhtiar's. The blessings of Khomeini, therefore, ensured the establishment of a new capitalist government over the head of the masses. In this way, it is obvious that what appeared as "the leadership of the Iranian revolution" basically played, from the beginning, the role of an instrument of bourgeois political counter-revolution, imposed from above in order to roll back the gains of the masses and to save as much of the bourgeois state apparatus as was possible under the given balance of social forces. The ruling class was as yet in no position to resort to further repression. Khomeini was, however, not offering all these services to play second fiddle. He was simply preparing for the takeover of all power at a more favourable moment. He represented a faction of the clergy that had been bent on establishing a more direct role for the Shiite hierarchy ever since the Mosadegh period. This faction, in cooperation with the then head of the secret police, made a move in the early 1960s for power, but failed. History was now providing it with an opportunity that it could not allow to slip away, especially given the fact that the bourgeois class was extremely weakened and hardly in a position to put up any resistance. The latter, with the approval of the imperialist master, had called on the clergy to save it in its moment of dire need by sharing power. What followed next in the post-revolutionary period can only be understood if the designs of the clergy for power are taken into account. In the beginning, the clergy did not have the necessary instruments for exercising power. The Khomeini faction did not even have hegemony inside the Shiite hierarchy. Many clerical heads opposed the participation of the clergy in politics. It could not rely on the existing institutions in the state either, since they were entirely unsuitable to clerical domination. Amongst other reasons, the bureaucracy itself was all opposed to clerical rule anyway. Even the Prime Minister designate, who was the most "Islamic" of all the bourgeois politicians, resisted any attempts by the mullahs to dominate the functions of the state. A period of preparation was thus necessary. With the direct backing of Khomeini, this faction first organised a political party, the Islamic Republican Party. This was simply presented as one newly formed party among others. Later on, however, this party squeezed out all the others and later replaced the Shah's single party. Through the networks of pro-Khomeini mullahs, it established an entire organisation of neighbourhood committees and Pasdaran units supposedly to help the government to keep law and order and to resist the monarchist counter-revolution. Revolutionary Islamic Courts were also set up to punish the Shah's henchmen. These courts quickly executed a few of the most hated elements of the old regime, but only in order to save the majority from the anger of the masses. The Imam's committees, the Pasdaran Army and the Islamic Courts, rapidly replaced the Shah's instruments of repression. All these moves were initially supported by the bourgeoisie, which realised that it was only through these measures that it could hope to finish off the revolution and begin the "period of reconstruction." The newly created "revolutionary institutions" were serving the Bazargan government well, constantly reassuring it of their allegiance to it. Later on, however, they became instruments of the clergy in ousting the bourgeois politicians from the reins of power and indirectly dominating the state apparatus. Khomeini also forced an early referendum on the nature of the regime to replace the Shah: monarchy or the Islamic Republic? Despite the grumbling of the bourgeois politicians, they had to accept this undemocratic method of determining the fate of the state, because the other alternative was the formation of the promised constituent assembly. The election of such an assembly during that revolutionary period would of course have posed many threats to bourgeois rule. The referendum was thus held and of course the majority voted for the Islamic Republic. The mullahs knew that the masses could not very well vote for the monarchy! It was later claimed that, since 98 percent of the people had voted for an Islamic Republic, hence the constituent assembly must be replaced by an assembly of "experts" (khobregan) based on Islamic law. The small assembly, which was therefore packed with mullahs, had of course a majority who suddenly brought out a constitution giving dictatorial powers to Khomeini as the chief of the experts. The clause of velayat-e faghih (the rule of the chief mullah) was resisted by the bourgeois politicians, but the clergy pushed it through by a demagogic appeal to the anti-imperialist sentiments of the masses and through the controlled mass mobilisations around the US embassy. The masses were told that now that we face "this major threat from the Great Satan" we must all vote for the Islamic Constitution. With an almost 40% vote, this became nevertheless the new constitution. Hence, Khomeini's clerical faction co-operated with the various bourgeois groupings in joint efforts by the ruling class to prevent the total destruction of the bourgeois state and in diverting and suppressing the Iranian revolution, whilst at the same time, always strengthening its own hand and trying to subordinate other factions to its own rule. It used its advantageous position within the mass movement to bypass the bourgeois state whenever it suited its own factional interest. But it was also forging a new apparatus of repression that was being gradually integrated into the state as the competition with other factions was being resolved in its favour. Contrary to the deviated analysis of the SWP leadership, at that time Ted Grant had a clear understanding of the nature of the Khomeini leadership and the role that it played and side with masses of people. This is what he wrote at the time:

And again:

Unfortunately the Marxists were too weak and could not play the role envisaged by Ted Grant. The Stalinists tail-ended the Khomeini regime, creating illusions in his democratic and progressive credentials rather than exposing him for what he was. Had there existed a powerful Marxist alternative things would have turned out very differently. In 1979 the Iranian workers could have come to power, providing the spark for revolution eastwards across the whole of the Middle East and westwards into Pakistan and India and beyond. Chris Harman, on the other hand, in his The prophet and the proletariat and the rest of the SWP leadership subsequently misrepresent the history of the 1979 revolution in Iran and the class nature of the Khomeini regime. By doing so, they have gone even further than Tony Cliff in revising Trotsky's ideas on permanent revolution. They have also added confusion upon confusion by totally misunderstanding first the nature of the Soviet Union and consequently the nature of such regimes as that created under Khomeini and that still survives today. Thus they mislead their own supporters and anyone who comes under the influence of their theories and thereby betray the interests of Iranian and international working class. ConclusionThe main political dangers of the SWP's position are as follows: Firstly, the SWP discredits the fundamental ideas of Trotskyism, Leninism and Marxism by revising the theory of permanent revolution. Secondly, the SWP will be forced to present the repressiveness of this regime as a secondary issue. Thus, in practice, it will side with a reactionary regime which has brutally eliminated the leaders of democratic movements of workers, students and women. With such a position any SWP supporters in Iran (fortunately there are none at the moment) would end up collaborating with a semi-fascist regime against the genuinely progressive forces. Thirdly, the supporters of the SWP in Europe end up by forming united fronts with supporters of Islamic groups such as Hezbollah and this would make it practically impossible for progressive forces in opposition to the present Iranian regime to enter into any activities with them. That is why the SWP is under constant attack by the genuine currents of opposition to the regime in Iran and cannot recruit even one progressive person to its organisation or ideas. Fourthly, the SWP will be used by Hezbollah activists in Europe and within the Islamic Republic of Iran to their own advantage to undermine the just struggles of the Iranian working class and socialists in Iran. Thus the SWP does a disservice to all genuine socialists struggling against Islamic fundamentalism. Attempts will be made to identify genuine socialists within the opposition to this dictatorial regime with the mistaken positions of the SWP and thus the credibility of all socialists is put at risk. For these reasons, the SWP leadership (or other organisations with a similar line of intervention in Europe and North America) should be exposed and isolated. So long as they side with or support the most reactionary regimes in modern history (under any pretext) genuine revolutionary Marxists should not enter into any joint activities with them. December 2008 [This article is based on the interventions of comrade Maziar Razi at the IMT World Congress, in Barcelona, August 2008. The article has been written for Marxist.com.] | |

No hay comentarios:

Publicar un comentario